9 min. read

Sneha Visakha is a Research Fellow at the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, Karnataka, working on Urban Development and Municipal Governance. She is interested in feminist urbanism, local governance and socio-legal research.

How does the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy’s research look at cities from a feminist perspective?

As a legal policy think tank, our research focuses on making better laws and guiding policy. In the Karnataka office, where I am based, we have a vertical which looks at urban development. We work with the urban development department of Karnataka on various projects, mainly looking at the municipal laws.

We face so many cases of sexual and physical violence in Indian cities with respect to gender, so sometime last year I spoke to my team to think about safety in the city from a feminist perspective. The intention was to think about how we can prevent violence not after it occurs but proactively. Currently, we aren’t really thinking about what creates the conditions and situations that lead to this violence. This was where the project started, building on feminist geographers who throughout history have written about space in such incredible ways.

Exposure to these theories was a revelation for me. When you start questioning who the city is made for, who is central to the ideation and design of the city, and think about the experience of women, trans people, or people from a marginalised background you come to realise the city does not think about the diversity of its inhabitants. We wanted to make the case for thinking about safety and notions of safety not from criminal law but from municipal law, incorporating a planning ideology that is based on the needs of different communities. So much of this work has to do with changing perceptions, so the Feminist City podcast we began was a way to start rethinking that narrative and get people to think differently.

Cities in India are among the least inclusive and equitable in the world. What are some core barriers faced by women in accessing certain urban spaces, and what are some examples of steps taken by cities to try to increase safety of female travellers?

I don’t even know where to begin. One book I would really recommend when thinking about women in cities here is Why Loiter by Shilpa Phadke, Sameera Khan and Shilpa Ranade. It focused on Mumbai and how women navigate the city. Women don’t occupy the city, they go from point to point, and safety is the main barrier to access to the city. The fear and perception of risk is so overwhelming that women will choose different kinds of opportunities and options based on this. Any woman who has grown up in an Indian city will relate to this. I’ve grown up in Hyderabad, I’ve lived in Delhi, and now in Bangalore. At sundown, you get calls from my family or texts from friends trying to know where you are.

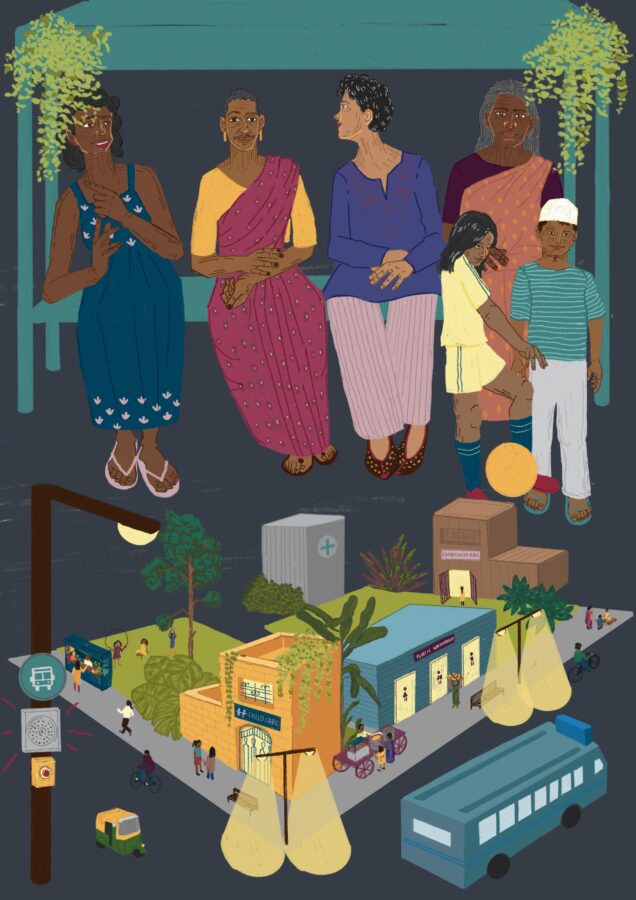

Understanding how different women use the city is also important to think about. Upper class women might have access to private vehicles but the majority of women will have to walk, and rely on public transportation and para-transit. In many Indian cities, there are very bad footpaths, as cities are so automobile centric. Women, who don’t have access to private vehicles as much as men, are already at a disadvantage in an automobile-centric city. So the way infrastructure is designed is a challenge in itself. There are also no public restrooms that are accessible. It makes it difficult for certain people to even occupy public space. Housing is also related to this, as well as lack of socialised childcare. These barriers have been normalised, and I think we need to first start recognising them as key problems that need to be addressed. A lot of the time, the narrative of greater safety emerges from increased surveillance and CCTV cameras. That doesn’t actually improve safety. Numerous studies have shown that more CCTV cameras, or more police presence actually don’t make women safer. The protectionist thinking doesn’t really help when a lot of the time women are scared of policemen.

A notable, positive example is the Delhi government making public transportation free for women through a pink slip campaign. To me, this is a huge way to make spaces safer for women. When you make public transportation free, you are encouraging women to use public transport and to come out of their homes. Safety is produced by people occupying this space. Jane Jacobs speaks about this dimension through her concepts of “eyes on the street”, as “natural surveillance” for example. In India, it’s a bit more complex as being watched is not always a good thing. There is such rampant honour culture and paternalism that there is a lot of scrutiny regarding young people interacting and intermingling. In larger public spaces however, where there is anonymity, having more women in that space will definitely make them safer.

In a op-ed you wrote last year, you framed the starting point to making cities equitable through gender inclusive processes with two dimensions: public representation in urban planning & taking feminist urbanist approach. Could you expand upon this?

The feminist urbanist approach I actually came across from a Barcelona based organisation called Col·lectiu Punt 6 that is doing fantastic work. It boils down to how we think about space. Space is not neutral, it is produced, and reproduces those ideological structures and social relations that influence its construction, in turn transforming or entrenching social relations.

To me, thinking about why women experience violence in the city, why our cities look the way they do, why there is such rampant inequality, was to understand the aims of urban planning. It’s important to make cities political, and to understand whose interests they are serving. The feminist urbanist approach asks questions as to who the city is made for, and what is the guiding ideology that drives the growth of cities. Currently, the answer to this is capitalism and patriarchy.

When we think about who we should centre when we plan or design the city, it’s not just about taking a gender lens, but also looking at the intersection of different identities and marginalisation. The focus should be on the everyday life experiences of people with these different identities and how urban planning takes them into account. Recognising that the people who use those spaces daily are the true experts is also critical. Planning has to be context specific, something that might work in one space might not work in another.

Understanding how women move through the city demands stakeholder engagement and recognising that trip chaining, care work, paid and unpaid labour journeys are key characteristics of their mobility patterns. Women in India also try to find homes closer to where they work because of dependencies on children and the home. Proximity is a possible answer for this, where key amenities such as grocery stores, hospitals, childcare facilities are accessible close by. I believe concerns around gentrification can be solved when you take a feminist approach, which touches upon class, caste, and re-centring planning for the most vulnerable people.

How do you see cost-effective transport modes like cycling help further women’s freedom and provide socio-economic opportunities?

The history of activism and cycling itself is tied to women’s struggles. The reason why women’s clothes changed was for example related to cycling. Women discovering the bicycle in the late 19th led to some degree of emancipation. In London, the Society for Rational Dress advocated for women to change what they were wearing so they could benefit from the freedom of movement and independence that cycling conferred.

So these movements are deeply interlinked. By allowing you to be mobile and independent, cycling is a feminist issue, as is public transit.

I cycle, I don’t drive, but it can be very difficult to cycle in Bangalore. The city is not designed for cycling, and for women, other barriers are significant. A large number of women in India wear Saris, that definitely are not the most comfortable to ride a bike in. What we need is a renewed social revolution where women should be comfortable wearing what they want based on their suitability. Safety is also a principle barrier. It’s almost impossible to navigate the city without being harassed. Those barriers are significant, on top of the socio-cultural perceptions and the infrastructure.

Cycling can also offer some really important opportunities for shorter distances. As much as women are reliant on public transit in India, there is a huge gap in the first and last mile. These lanes need good lighting, designed in such a way to facilitate cycling and accessibility. Bike share systems are popping up, but need to be unlocked with a smartphone, which already excludes a portion of the population. Inevitably, there are class and caste dimensions that disempower women from the communities that most need cheap and reliable transportation.

Integrating transport modes and repurposing street space are key to incentivise people to stop driving private vehicles. Could you speak a bit about the legislation, if any, that comprehensively deals with urban transport in Indian cities? How do you think such agencies can better integrate the needs of women in transport planning?

One of the first issues I started working on is how so many transport agencies are involved in mobility management. Firstly, there exists a policy problem. There is a really fantastic book, Installing Automobility, by Govind Gopakumar, who talks about automobility as a phenomenon that is being exported in Bangalore, where cars are the central element around which the city is designed and not the people. This is the problem that relates to imagining what a city could ideally look like. Bangalore should not reflect Singapore or Amsterdam. There shouldn’t be notions of what the ideal city should look like. The ideal city is simply the most equal city. So the policy issue here relates to de-centring the automobile from transport planning. Until we remove the volume of cars in our cities, people won’t have the adequate space to move.

Addressing this needs to happen through greater representation and participation of people in the planning process. For instance, in Bangalore, the nodal agency for planning is the Bangalore Development Authority, not the Municipal Corporation. The latter has people’s representation, but a parastatal body is doing the planning. With respect to the number of agencies involved, there are calls for a unified metropolitan transit authority like Transport For London. It’s unbelievable that this institutional interaction is not already happening. How can one authority decide on bus routes when the other one is building the bus stops? There needs to be commonality.

In regards to the needs of women, it fundamentally boils down to people assuming that gender is a specialisation that only certain departments are concerned with. Every aspect of the city planning should integrate urban sociology and feminist geography. It’s not just about having technical capacity, but involving people that are trained in the feminist methods to make key decisions. There is a critical need in Indian cities to empower Ward committees, where people in a particular locality can make decisions about the ward’s development. Taking into account people throughout the urban process is so important. It’s through participatory and procedural democracy that we can realise the women’s right to the city.

Beyond legal change, it’s also about social and perceptual change. It’s not just about getting women in the room, but also getting the experts to listen to the experiences of women. You might have spent 5 years studying the subject, but these people have been living in the area for decades. This will lead to more equal cities while also changing the nature of social relations.