Filip Watteeuw is a senior deputy mayor in the city of Ghent, Belgium. He is responsible for Mobility, Public Space, and Urban Planning. Filip has been a leading political figure in Belgium and Europe, known for his transformative approach to urban planning. He played a key role in implementing the circulation plan in Ghent, which aimed to prioritise cycling and pedestrian infrastructure over car usage. Under his leadership, Ghent has become a cycling city, with a significant increase in cycling rates and a decrease in car usage. Filip’s bold and innovative approach to urban mobility has garnered international recognition and serves as an inspiration for other cities looking to prioritise sustainable transportation options.

–

As a leading political figure in Belgium and across Europe, you have spearheaded the transformation of Ghent in less than a decade with your bold urban planning approach. What inspired Ghent’s Circulation Plan?

I became the deputy mayor in 2013, and we wanted to become a cycling City like some other iconic cycling cities in Europe such as Copenhagen, Groningen and Utrecht. I visited those cities in the first months of my first term as a deputy mayor and what I saw there was really incredible. These are such strong cycling City cities with a high level of quality of life, but with really sustainable, strong mobility policies. I was really impressed by the infrastructure and by the policy makers. My second thought was, “how is it possible to reach the same level? How can I do it? I only have six years as a deputy mayor in Belgium. I have only six years and it is impossible to even reach close to that level.” I also didn’t have the budget to reach the same level because the infrastructure in those three cities was so marvelous – I didn’t know how to reach it.

Then we started to think with a group of people in the city administration and my collaborators: How can we become a cycling city without the time and budget typically needed? We realised that becoming a cycling city is not just about infrastructure or innovations; it’s about the battle for space. It’s about giving space to cyclists and pedestrians.

What cities like Copenhagen, Utrecht, and Groningen did was give space to cyclists by building infrastructure, and they took the time to do that. But if you want to go faster, you can give space to cyclists without the infrastructure. The big space monster in cities is the car, which takes up most of the streets and squares. In a typical city street, between 65% and 85% of space is allocated to cars. By taking some of that space, you create the room needed for cyclists and pedestrians.

That’s what we did with the circulation plan. We didn’t have a large budget; the 2017 circulation plan cost about five million euros, which isn’t a huge amount. So, we took the space by eliminating through traffic. Honestly, I copied the circulation plan we used in Ghent from another city.

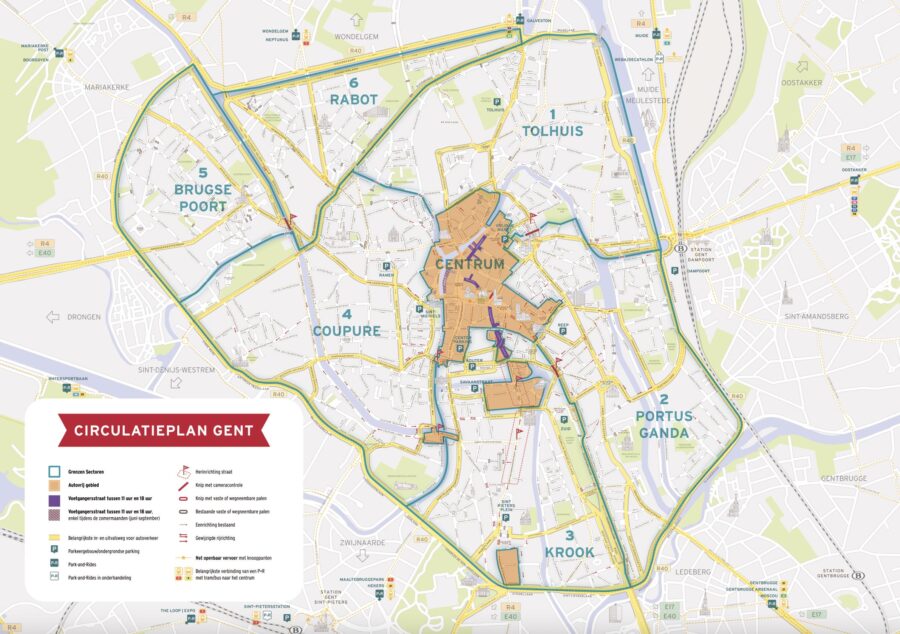

Groningen had the same circulation plan implemented in the 70s of the former century. So it means that we are doing what we have implemented our circulation plan on a bigger scale than Groningen but it’s the same thinking if you want to get rid of the true traffic, you must make it impossible to drive with a car just through the city without a destination. So, in the middle of the city, in the real heart of the city center, we have a car restricted zone. And around that car restricted zone we have six other zones and it’s impossible for a car to get from one zone to another except if they take the ring road. So if you want to go from one zone in the west to a zone in the east, it’s impossible to drive through the city, you have to take the ring road.

Before the circulation plan, we conducted studies and discovered that about 40% of car traffic during rush hour was through traffic—vehicles without a destination in the city. These cars would start in the city center and head south without taking the Ring Road, driving through the city instead. Making this through traffic impossible freed up space.

In 2017, we implemented the circulation plan, and the results were incredible. We suddenly had space for cyclists and pedestrians, making the area safer. We saw a significant increase in cyclists: the mode share for cycling rose from 22% in 2012 to 35% in 2017, a 13% increase in less than one year.

We also saw a 12% increase in public transport users after implementing the circulation plan. This is a significant increase, and these changes are very important. Before the plan, opponents, mostly car drivers, argued that we needed to improve alternatives before implementing the circulation plan. They said, “If the alternatives are good, then go ahead with the circulation plan.“

What I saw in 2017 was that it’s not right—it’s even a bit of nonsense—to say that you need to improve the alternatives before implementing the circulation plan. When you implement the circulation plan, the alternatives actually get better because you create space for them. Public transport improved, cycling improved, and walking improved. It goes against intuition. Your intuition might say that you need to improve the alternatives first, but that’s not the case. A good circulation plan makes the alternatives better by giving them space. That’s what we did.

Behaviour change often faces resistance, especially when it involves bold measures like limiting car use, as shown in step one of the circulation plan. So I wanted to ask how you adjust your resistance from car use users and successfully promote cycling as an alternative.

Yeah, that’s something I put a lot of energy into. I resisted the opposition, but I also made many mistakes. The first sketch of the circulation plan was created in October 2014, and we implemented it in April 2017. So, we had two and a half years of preparation time. That period involved many evenings and countless moments of talking and discussing with people, citizens, and residents. During those two and a half years, I was hardly ever home. Sometimes my wife asked who I was because she didn’t see me much. It was very intense and rough.

Initially, the first weeks and months were rather quiet, but as resistance built up, it became rough with yelling and shouting. I even received death threats and had six weeks of police surveillance. That was really hard, especially when they threatened my family. That was very, very hard.

My strategy was to talk, talk, talk, and never give up, never back down. I would try to reach everyone, knowing it was impossible to please everyone. The only thing I could do was to talk as much as possible. However, the two big mistakes I made were trying to argue with people using scientific, rational facts instead of telling appealing stories. At many conferences and congresses about mobility policy, experts use Excel spreadsheets and graphics, but that’s not appealing to people who need to change their behaviour. I always say that what I did was talk, but what I should have done was tell stories, and that was my first big mistake.

My second big mistake, and the mistake of the entire city government, was treating our circulation plan as just a mobility project. I was responsible for mobility in Ghent, and everyone in the city government at that time was a bit afraid of what would happen with the circulation plan. They kept their distance, thinking that if the implementation was a disaster, they could say, “Oh, it’s his responsibility, so it’s his mistake.”

We should have viewed it not just as a mobility project but also as an economic, social, and cultural project. It should have been broader. At that moment, we could have seen opportunities across different stages, where various domains could have strengthened each other. But we didn’t; it was purely a mobility project. What we should have done was collaboratively work to change the city for the better.

I said I made two big mistakes, but there were more. Another mistake was that I didn’t recognize and activate the people who were in favor. It was a period of really hard work, and neither I nor my collaborators had the time. I focused on the resistance and the debates, thinking everyone was against the circulation plan, but that wasn’t true. The people who supported us were there, but they trusted what we were doing and thought, “Why should I make noise? I’m pleased with what’s happening.” So, at times, I felt really alone in this battle, but that wasn’t true. Many people were in favor. There was even an organization that organized a manifestation for those in favor, which was bigger than any protest by the opponents.

One of the strangest moments in my life was after the implementation on April 3, 2017. I had an appointment with a journalist at 11 o’clock. The journalist asked, “Can we take a bike ride through the city?” I hesitated because I thought it might be risky, given the opposition to the circulation plan. If someone at a crossroads started yelling at me, insulting me, or threatening me, it would be on the front page of the newspaper. After some hesitation, I said, “Let’s go,” and we did it. The strange thing was that I only received thumbs up, congratulations, and thank yous. I thought, where were you all those years when I thought there were only opponents? The journalist even asked me at the end of the bike ride, “Have you organized this? We only see people who are in favor.” But I hadn’t! I should have also activated the people who were in favor, and I didn’t do that.

I can imagine the relief you must have felt at that point.

Yeah, I felt two things. I felt relief, of course, but also at the end of that day, for the first time, I felt how tired I really was and how much energy that costed. I was relieved but very very tired.

I think it’s because all this time you’re in this fighter mode, you think there’s so many opponents and you’re fighting against them and when you realise that there’s so many people who are in favour of what you’re doing, your body feels like it can rest.

Yes, that’s for sure. And what is important is that the circulation plan is working very well. There were some minor problems, but that’s normal. We adjusted some things and Ghent has become a very attractive City. It was already a beautiful medieval city and it became more attractive. If you look at the vacancies of the shops in Ghent, you see that we are doing quite well here in Flanders. We have some studies and what we see is that Ghent has the lowest vacancies of shops in all of Flanders. This has to do with the fact that the world changed. When I was 20, if you wanted something special you had to go to the city because in my village where I was born there was nothing, but that has changed because everyone has a laptop and the moment you want to buy something, you don’t have to be in the city, there’s e-commerce and so people can can buy whatever they want, whenever they want, wherever they are. What is important in the city now is the quality of life and the experience in the city to walk around, stroll around and look at the architecture, look at the shops. And if there are practically no cars in the neighborhood then it’s pleasant to walk. If you have to pay attention to every step you take, then it’s not so pleasant. And so that’s important.

I want to dive a bit more into what this means for the city. As I mentioned, the theme of Velo-City this year is connecting through cycling. What does this mean for Ghent and how does cycling bring people together?

Every morning, when I arrive at City Hall, I bike through the streets and instantly form a community with other cyclists I encounter. We greet each other, share moments together—it’s a sense of togetherness. In Ghent, we even experience cycling traffic jams, cycling congestion, which is pleasant because you’re in a group where you can converse. Compare that to being stuck in a car in traffic, where everyone is isolated, each trying to get ahead of the other.

Cycling creates connections between people. Ghent was the first city in Belgium to introduce a cycling police unit, meaning direct interaction with officers on bikes. They are accessible in ways car-bound police are not, enhancing community engagement. That’s why cycling means connecting.

Something you’ve mentioned on occasions is how a city’s best car plan is a bike plan. Can you elaborate a bit more on this notion and how this can help more people to start cycling.

Yeah, it’s because, several times during debates and discussions, there was the remark from some car drivers that cyclists are taking the place of the cars. It’s a bit of a competition between cars and cycling which is a pity because everyone who makes the shift from car to bike, makes space for people who really need the cars. What we try to do is to get people to use the bike, but it’s not against cars. We know that some people need their car for several reasons. It’s not against cars, but if you want to have that quality of life, if you want to have that safety and if you want to have a space for everyone, you need to shift to a bike. So if you want to have better car mobility, you need to have the bikes and a bike policy. If we could experience that all our cyclists and all the people come together on a certain day by car instead of taking their bike, then everything would be a traffic jam and no one will reach their destination. So, bikes are very important for Mobility.

You mentioned that many cities are inspired by other cycling countries like the Netherlands and Denmark, but they’re often discouraged by the time and infrastructure investments that are needed, as well as the limited funds available. What advice would you give to decision makers, politicians, local leaders, or other stakeholders who are hesitant about considering cycling as a viable transportation option for their city?

It’s not just about infrastructure; it’s about creating space. Of course, we have also invested significantly in infrastructure. Over the past 12 years, since I became deputy mayor, we have built about 45 cycling bridges and underpasses, totalling more than 100 kilometers of cycle paths. This investment in infrastructure has been substantial for us, but we’ve also focused on nurturing a cycling culture.

The advice I give to other cities seeking real change is this: policymakers must understand that it’s not about isolated projects or infrastructure improvements alone; it’s about transforming the entire system. If you want to reduce the dominance of cars and truly become a cycling city, systemic change is essential.

Another piece of advice is to work on multiple fronts simultaneously. Implementing a circulation plan or improving cycling infrastructure alone is not sufficient. We have also prioritised measures like our successful car-sharing program. When I started as deputy mayor, we had around 100 cars and 1,500 members in the car-sharing organization. Now, we have more than 23,000 members and over a thousand cars. Car sharing plays a crucial role in sustainable mobility policies because it reduces car ownership. For instance, in 2015, we averaged 1.2 cars per household; by 2021, this had decreased to 1.0 cars per household. This reduction not only enhances quality of life and safety but also supports social equity by providing access to transportation without the burden of ownership, particularly beneficial for financially vulnerable individuals.

Additionally, our approach includes reevaluating parking strategies, removing approximately 8,000 to 8,500 parking spots in the last six years. We have also implemented pedestrian plans to promote walking and developed a mobility poverty plan, recognizing that not everyone has equal access to mobility options.

It’s not about getting in the newspapers and so on. You will get in the newspaper if you have mobility in your responsibilities, but be bold. Dare to take decisions, dare to build things.

What about when the attitude or the mindset is a large barrier – How do you suggest cities address this mindset?

That’s very difficult because you can’t change the mindset of a city on your own. It’s not just the city; it is the region, the country, and the media that all play a role. In Ghent, we try to show pedestrians and cyclists that they are the most important road users in the city, though it’s not always easy. One of my favorite actions by the Cycling Embassy of Ghent is an activity in which they give cyclists the opportunity to pump up their tires, clean their chains, and grease them. It’s a simple service, but it demonstrates that cyclists are valued. This inexpensive and straightforward action sends a message: “Cyclists, we appreciate you, and we want to support you because you are important.” That’s the essence of cycling culture—showing that cyclists matter. Setting examples is also crucial. When people see their neighbours, government officials, CEOs, and entrepreneurs cycling, it inspires them. If they can cycle, others might think, “Maybe I can do it too.” These examples are very important in changing mindsets.