Amsterdam, August 3rd, 2020

Cities across Latin America have recently implemented extensive networks of pop-up bike lanes. In this piece, Felipe Caicedo Otero engages with Bicycle Mayors from Lima, Quito, Tulancingo and San José on the role of civil society in ensuring that this infrastructure is made permanent.

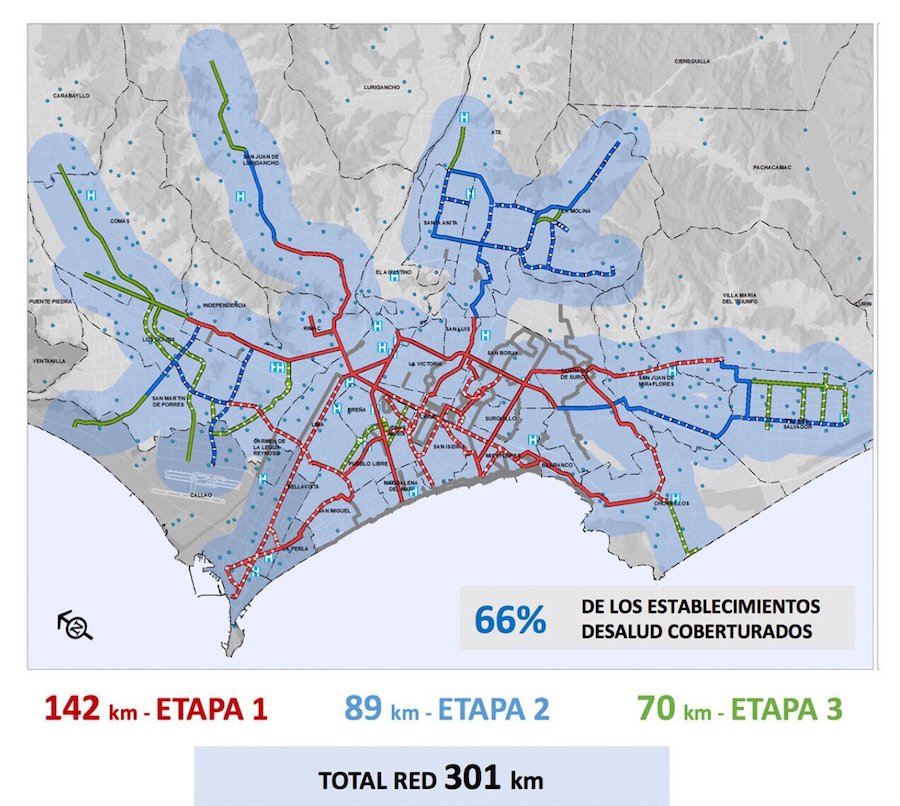

The lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic has created a dual threat, in which citizens increasingly need to resume their normal activities for economic survival, while at the same time risking the consequences of a new spike in cases. The solution to this in part lies in ensuring safe, socially distanced transportation options. Across the globe, city governments have taken measures to promote active mobility by creating safe spaces that invite even the most sceptical citizen to adopt the bicycle. In Latin America, where citizens barely imagined cycling could gain as much importance, cities are also experiencing cycling levels only thought of as utopian for many. Mexico City has implemented 20 kilometers of bicycle lanes in Avenida Insurgentes, one of the city’s main and longest avenues, and another 14 kilometers throughout Eje 4 Sur. Bogota started the pandemic with 117 kilometers of temporary bike lanes, and is currently in the process of making permanent 21 kilometers to expand its total network of bicycle lanes to 572 kilometers. The Mayor of Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic created the Bicycle Office, as part of the local government, and is piloting the first 8 kilometers of temporary bicycle lanes. The government of Lima, Peru, is planning to implement 301 kilometers, a plan that was initially thought to be finished in 5 years that the pandemic accelerated to an expected time of completion is 3 months (see image 1). The project in Lima is also thought to solve a connectivity issue of the current bicycle lanes which are isolated from each other and not part of a network that provides safe, direct, and meaningful routes throughout the city. In Quito, the capital of Ecuador, the city created 25 kilometers of these lanes watching closely the integration of this network with the city’s public transport.

The increase in interest in bicycle infrastructure that governments in Latin America are showing is a direct consequence of COVID-19 and the urgent need to provide safe, affordable and efficient means of transport to its citizens. However, once confinements ease, there is a risk that public transportation and especially private vehicle usages will resurge again. This raises two questions: what will happen with all these kilometers of temporary bike lanes? What role does civil society have to play in the post-pandemic fate of the temporary bicycle infrastructure?

We asked four of our Bicycle Mayors in Latin America for their opinion on these questions to understand the reality of the continent and offer insights to fellow bicycle advocates in the region.

The Fate of Temporary Bicycle Lanes in Latin America:

David Gomez, Bicycle Mayor of San Jose, Costa Rica, considers that there are two possible outcomes for these temporary lanes. In cities where bike lanes have been framed under a broader network of mobility infrastructure that is inclusive with the bicycle and has public acceptance, it is very likely that those spaces become permanent. On the other hand, he worries that in cities where bicycle lanes are only thought of as a way to temporarily reduce the journeys in public transport and there is ongoing conflict with motorized road actors, there is a risk of disappearance.

Javier Flores, Bicycle Mayor of Lima, Peru, shares that there has been a rising excitement for bicycles and the urgency of the situation has pressured authorities to rapidly implement bicycle lanes in an unprecedented manner. He considers that such temporary spaces can become permanent under four circumstances:

- Bicycle lanes need to have a planning process behind them and should be part of a network that allows getting from A to B, efficiently. Bicycle lanes that are implemented out of nowhere and have no clear destination or connection points are not sustainable in the long run. This absence of integration to a city’s network won’t attract citizens to use it as it doesn’t provide any added value to its users.

- If, during the existence of these temporary lanes, citizens can experience the kind of city they want and showcase the bicycle as a tool for social transformation through the implementation of bicycle infrastructure, there will be greater interest to keep it.

- Citizens continue to use the spaces. Monitoring usage of bicycle infrastructure provides objective data to make informed decisions on the fate of these spaces and make the most efficient possible use of public spaces. The city of Bogota, for instance, decided to remove portions of the lanes considered in the initial plan of temporary bike lanes as it was identified that the existing lanes in those points were enough to hold the demand of cyclists. Monitoring usage also provides measurable arguments to why bicycle lanes are needed – or not – in specific areas. Bicycle data can be used as a tool for political advocacy and an inspiration for citizens. It helps feed the sense of being part of a greater community as current and potential bicycle users start to realize they are not “alone in this”.

- A consistent political agenda towards bicycle infrastructure from upcoming governments to avoid that changes in politics also become a threat to the sustainability of bicycle policies and programs.

Diego Puente, Bicycle Mayor of Quito, Ecuador, is optimistic that bicycle infrastructure will become permanent as a natural consequence of the rising users of those spaces. However, that natural course of events will happen only if temporary bicycle lanes are planned appropriately which will require that four aspects are taken into consideration: connectivity, comfort, safety, coverage.

If the four aspects are taken into consideration and well addressed, bicycle infrastructure will not only become permanent but it will rapidly require expansion to support the increasing number of users: “build it and they will come… but build it properly.”

Ricardo Bravo, Bicycle Mayor of Tulancingo, Hidalgo, Mexico, is also seeing an increase in the number of people moving around by bicycle. This growing number of users and advocates has the potential to ultimately lead to the realization that cyclists can be a strong electoral base and aspiring politicians will start creating plans to address some of the most pressing issues related to the facilitation of active transportation.

The Role of Civil Society:

David explains that civil society plays a key role as users of these spaces. If these spaces continue to be used after the pandemic, city governments won’t have other alternatives than to make those permanent. As more citizens use these spaces, decision makers and politicians will be interested in making improvements in the quality of these spaces. Better spaces also invite more citizens to use it which will continue to expand the number of bicycle users. As users continue to grow, decision makers will be more willing to openly discuss and plan improvements of these spaces. The result is the creation of a virtuous circle of constant improvement of bicycle infrastructure and growing of bicycle users. There is now a greater consensus that cities become more resilient with mobility systems built around walking and cycling, and this revived awareness can be capitalized to make permanent the reclamation of street space.

The pandemic has put many bicycle movements in the spotlight, and Javier shares that bicycle advocates can now play a more central role in promoting cycling by leading actions to incentivize it. The objective of this, besides securing permanent space for cycling, is to increase grassroots advocacy and citizen participation with local authorities, in order to think and design public policies that integrate citizen perspectives.

Diego believes that if the four criteria (connectivity, comfort, safety, coverage) are met, a critical mass of users will emerge. In this sense, the role of advocates is to guide and support new users in their transition from motorized to cycling mobility. Furthermore, civil society stakeholders should also guide local authorities. Local governments in Latin America often lack knowledge around the reality of cycling mobility in their cities, whereas cycling advocacy groups and organizations do. This creates a responsibility to engage with local authorities to paint the real picture of cycling in the city in order for public policies to respond to the true needs of citizens.

Civil society’s role is crucial to raise the social status of the bicycle, expresses Ricardo. In Tulancingo, as in most Latin American cities, cultural misconceptions around the bicycle inhibit citizens to opt for this mode of transportation even if their daily commutes are less than 3 kilometers. Cultural misconceptions around cycling are still present and shape the approach that local politicians take when addressing bicycle-related issues. Seeing the bicycle only as a recreational activity, assuming few people are willing to move by bicycle, and considering motorized mobility as the main transport option, are some of the misconceptions around bicycling in Latin America. An improved socio-economic perception the bicycle will reshape the way public policies around mobility and infrastructure are addressed. Civil society stakeholders and advocacy groups can address this through well designed communication and awareness campaigns.

Citizens thus clearly have the power to drive positive changes in our cities and this power relies on actions as simple as cycling to work, to engaging with local authorities for the design of cycling policies, or to the creation of community-led pop-up bicycles lanes. We all hold this power and how we use it will determine the fate of temporary bicycle infrastructure in a post-pandemic context. Using the temporary lanes and inviting or guiding others to do it is an immediate action that can have positive long-lasting effects in the creation of more livable and sustainable cities. If your local government is characterized by taking reactive rather than proactive measures, work on increasing cycling users in the temporary spaces which will lead to the reaction of making the spaces permanent.

Furthermore, communicating specific and relevant benefits of the bicycle to our communities is a way to elevate the social status of the bicycle and get local authorities excited by the idea. This is a time to be specific, shifting from a general communicative approach (i.e.: bicycle is good for your personal finances) to a context-relevant approach (i.e.: cycling 3 kilometers in your city will save you $4.00 USD a day).

Every substantial change in the promotion of cycling across the world was sparked by committed citizens with a firm belief who were able to transmit that feeling to local authorities that held the right political will. This was true of Amsterdam in the 1970s, as it will be in the many cities being transformed today. The political will is here, and it is more crucial than ever to keep believing, keep inspiring and keep cycling.